FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

NEW YORK CITY, NEW YORK, April 22, 2020—Debra Schimdt Bach, curator of decorative arts at the New-York Historical Society, said she wishes all of her Zoom conferences ended with a group ho-ho-ho with 20 Santas.

Entitled “Sit (Virtually) at the Desk of Clement Clarke Moore,” the talk was tailored to educate the New York City Santas, a new chapter of the International Brotherhood of Real Bearded Santas (IBRBS).

During the pandemic, the NYC Santas have organized other virtual meetings open to Clauses throughout the nation. This 30-minute program was the first dedicated to Moore, who is credited for writing “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” better known as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

To illustrate, Bach showed archival photographs of the “secretary/chest of drawers” that most likely belonged to Moore and most likely was the very piece of furniture on which he wrote his famous poem.

“We believe it belonged to Moore and we believe that he wrote the poem,” Bach said.

The poem first appeared anonymously in the Troy Sentinel in 1823. Moore was not publicly attributed as the writer until 1837 when it was included in the New York Book of Poetry. He acknowledged authorship in 1838 and published it under his name in 1844.

So this time lag between when it first appeared and when he took credit has led to debate.

Moore was an Episcopalian minister and professor at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan. Moore donated some of his inherited estate, called Chelsea, to the seminary. Other pieces of his property eventually formed Chelsea, the West Side neighborhood that still bears its name. Could Moore really have authored this beloved piece of American literature? Or was it someone else? According to Bach, most scholars believe Moore wrote the poem based on the syntax of his other writings.

Legend has it that Moore first recited it at his Chelsea home on Christmas Eve 1822 to entertain his many children. A theory is that a young Harriet Butler from Troy, New York, was also at that reading and recorded it in her personal copy book. Her father and Moore were close friends and fellow ministers. One of Harriet Butler’s brothers was named Reverend Clement Moore Butler, making her a leading candidate as the one who submitted the poem to the Troy Sentinel the following year.

“She was very much enamored with the poem,” Bach said of Harriet Butler, adding that the desk was donated to the New-York Historical Society in 1956 through Butler’s family. She never married. The item was handed down the family line through a cousin.

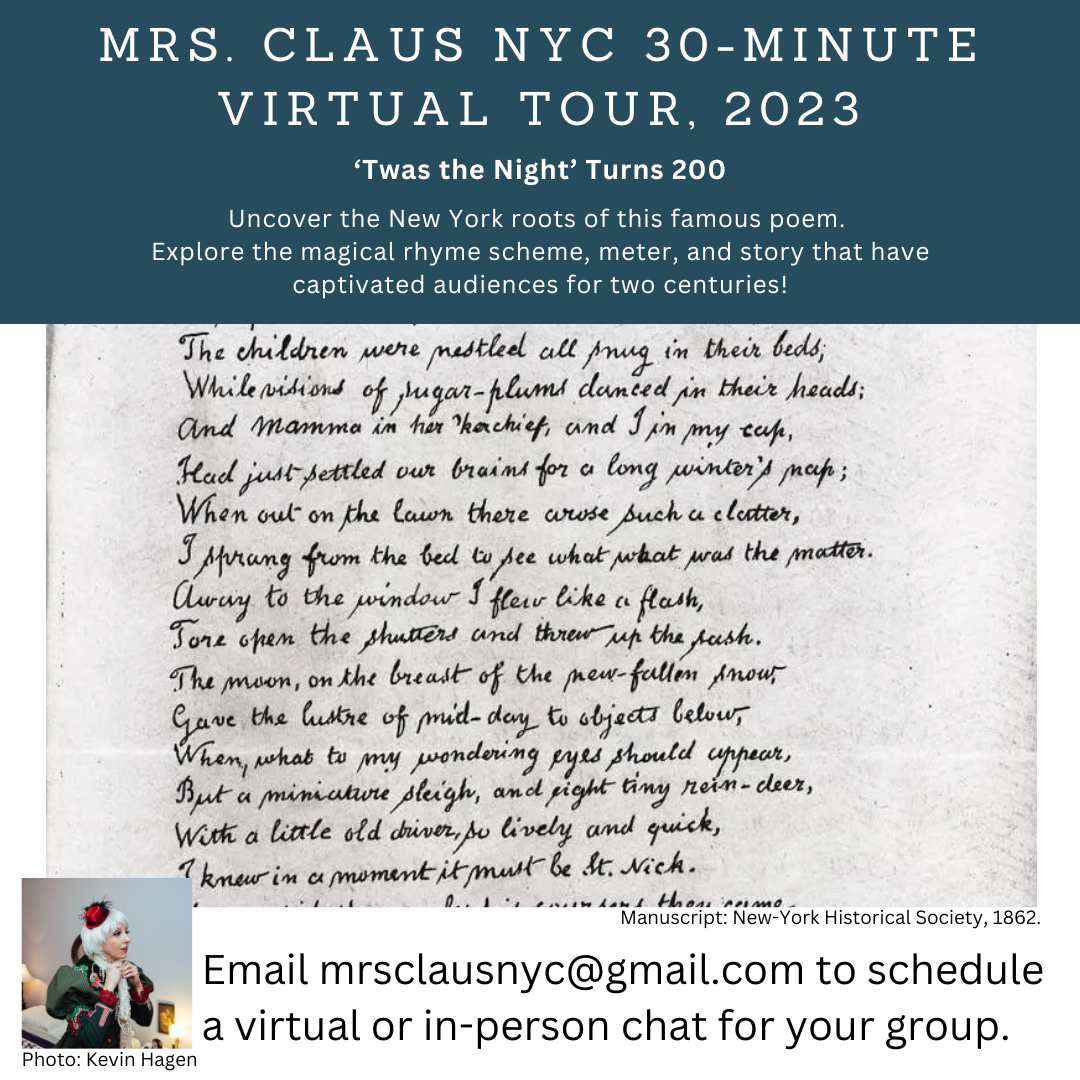

Bach also showed a handwritten black and white copy of the manuscript signed and dated by Moore in 1937 as a gift to the New-York Historical Society. Also in the society’s collection is an 1837 painting by Robert Walter Weir, entitled St. Nicholas, that depicts a fireplace and an elfin figure with his finger alongside his nose. One of the Santas in the talk noticed a broken clay pipe at the figure’s feet, which Bach attributed to a Dutch tradition of breaking pipes on St. Nicholas Day (December 6).

The painting reveals a “merging of ideas and influence” that developed a “public legacy” of a jolly character rather than the dour religious image from Europe. It also reveals a cultural movement meant to preserve New York’s Dutch heritage. Weir may have been inspired by Moore. Moore was certainly friendly with writer Washington Irving. Irving’s Knickerbockers History of New York first depicted a comedic version of St. Nicholas. In 1835, Irving founded the St. Nicholas Society, a social club for male ancestors of Dutch colonists.

“Despite the fact that St. Nicholas was a Catholic saint, it appears that early Dutch New Yorkers really stayed true to celebrating St. Nicholas and revering him as a patron of children, as a patron of New Amsterdam,” Bach said. “I’ve also read that he was the patron saint of the greater colony of New York, although I’ve only read that in one place.”

In her research for this talk, Bach discovered that St. Nicholas is also the patron saint of her place of employment, the New-York Historical Society.

“I think certainly St. Nicholas as we know him was a New York invention,” Bach said during the Q & A. “So, yes, it does appear that the whole idea of celebrating St. Nicholas in a very whole-hearted cultural way may have originated in the United States in early colonial New York.”

-###-

You may go to YouTube for a recording of the talk that took place April 22, 2020.

Related Article: NYC Soars With Its First Chapter of International Brotherhood of Real Bearded Santas

Related Article: Let’s Stay Together While Six Feet (Or More) Apart